Katalin Hetey: Steel Sculptures and Graphic Works.

Exhibition at the Mono Gallery, 7 May-6 June 2009.

Not long ago a new venue, the Mono Gallery, opened on Ostrom Road, which runs steeply up the north side of Castle Hill in Buda. Its declared intention is to show the work of contemporary artists, including most emphatically sculptors. In May 2009 the work of Katalin Hetey was on view, of a double pleausere for art lovers. Hetey’s sculptures are rarely shown in Hungary, and yet she is one of the most important of contemporary Hungarian sculptors of our time. This was a chance to honour one of the country’s least known creative artists. Hetey left Hungary in the wake of the 1956 revolution, and for 25 years even fellow-artists heard little about her, though by the eighties she was already being allowed to show her work and, indeed, she even moved back to Hungary. That, though, was only to remain modestly int he backround: retrospectives of her work were arrenged in provincial cities (Miskolc, Győr), in Budapest, however, she featured mainly in group shows and small solo exhibitions. Those, along with a high-quality album and a catalogue of her work, both published in 2005, were enough to make her name, and even win her e degree of ceognition (she was awarded a Kossuth Prize in 2009), but a real breakthrough to a wider public, which she deserved, would have needed a big one-man exhibition in Budapest. The Mono Gallery, restricted to the limitations of what was possible for them, showed only a small and focused segment of the whole oeuvre, with the goal primarily of arousing attention and paying respect to an artist, who will turn 85 this year. From 1942 to 1947 Katalin Hetey studied painting under István Szőnyi at the Budapest Academy of Fine Arts. Fort he next ten years she taught drawing and art history at the Fine Arts Gimnázium, taking leave of the country at the end or 1956. The first stop on her journey was Italy, where the world began to open up for her, giving her the chance to meet major figures in the art and literary scene such as the sculptor Marino Marini, the writer Ignazio Silone, and Alberto Burri, a leading painter of the Arte Povera movement of the sixties. She also made friends with the writer Francois Fejtő and his wife and, with their help she settled in Paris in 1957. The dynamic artistic environment transformed her art: from a painter, she became a sculptor. Looking back over what is now more than half a century, one has the feeling that it could not have happened otherwise for such a sensitive and open artist.

In order to make a living , she took on works as a graphic artist and illustrator and later again she taught drawing , but all the time she maintained her connections with the art scene, entering competitions and attending conferences on art. She engaged strongly with the world around her. She held her first one-man show in 1962 at the Galerie Lambert in Paris, and the next year she won a scholarship offered by the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving, which allowed her to work for a year in California and New York. From then on there was a whole string of shows: Washington D.C,, Los Angeles, Hamburg, Schiedam (the Netherlands), Paris all prestigious venues, and she was also among the participants at the International Biennale for Young Artists at Tokyo. She became a French citizen in 1970, a year which also marked a turning point in her work. At an exhibition in Lausanne she made the acquaintance or the owner of the Galerie Schlegl in Zurich, who offered to take on not only her but also her husband, the painter Tamás Konok – a co-operation that lasted until Schlegl’s death 22 years later. One of the conditions of the deal was that the two artists should spend part of the year in Zurich, and from that point onwards her life was divided between Paris and Zurich. While working in Zurich, she made regular visits to a foundry int he nearby small town of Aarau, which is where the small scuoptures that make up the series Part and Whole were cast. This could indeed be considered her chef d’oeuvre, as she began the series in 1970, and to this day she is still adding to it. It was in this that she hit upon the kind of sculpture and one formal world that gave her the personal voice with which she could address not just the art of our day but also its philosophy. In order to get at its essence, however, it is necessary to review the path which led her here, namely, the part of her career between 1957 and 1970 taking her from the problems presented by two dimensional painting to sculptural form and the fundamental issues of space.

The two decades of this period were years of this period were years of major expansion in sculpture, a process reflected in writings on the history of sculpture as something quite independent of that of painting, with more books being published about sculpture than had appeared in the half century before. Quite apart from strictly art-historical surveys , there were also surveys that took a particular line in grouping and analysing works in relation to the inherent laws of form such as mass and sculptural volume. This was when critical writings began to record the process through which the art of modern sculpture was born, with the art of forming mass turning into the art of forming space. The change in approac was no doubt assisted by fact that the big metropolises of Western Europe, in seeking to rebuild after the Second World War, had ever greater aspirations to integrate modern sculpture and offered to artists large-scale commissions like never before. All the arts strove to think in terms of spatiality. With even painters stepping out of planarity to concern themselves eith the possibilities of three-dimensional modelling, the moulding of the immediate environment, the aesthetically organised relationship of abstract form and space, of colour and space, became central issues.

The sixties were a time of interaction between art and industry and the growth of industrial production gave design a huge boost. The call for a modern, artistic moulding of functional objects came to be taken for granted, and artists were thrilled to discover industrial rationality, the beauty of mechanical structures. Sculptures emulated the aestheitc of machines, with public arenas sprouting sculptures of highly polished metal, mechanically operated mobiles, and enormous , cheerful works of plastic art composed of brightly coloured tubes. In complete contrast, the other major movement of the time, Art Brut used ordinary materials without regard for traditional ideas of what was aesthetic, showing the other side of modern industrial society in all its brutal rawness, the singular „aesthetic” of rubbish and scraps of waste. So art, even as it strove to create –cut, lucidly arranged, logical order of structured spaces through a new interpretation of the relationship between space and mass, was turning with avid interest to everything that was its opposite: of the moment, unpredictable and chaotic. The material of such works seems to live a life of its own, with lacerated, crumpled surfaces and compressed masses collecting within themselves and re-radiating the external forces which formed them. There is no regular form or reassuring plane to be seen. Artists discovered the beauty of the world of the objet trouvé, scrap metal and rusting engine parts. The fringe of life encountered the peak of art. Katalin Hetey grasped both, resolving the contradiction between them by organising chaos indo structures.

Like many other sculptors, she made the rounds of scrap-iron yards, photographing them and collecting interesting objects. She was attracted to chaotic heaps of formless forms, sensing that they contained poetry despite the brutality and aggressiveness of their appearance. She emulated this in her own works, assembling large-scale photomontages and collages of crumpled paper, fashioning sculptures out of press-moulded metal pieces that she came across. She was passionately interested in materials, malleable plaster most especially, shifting of its own accord (e.g.by dripping) at even the gentlest touch of the hand. She produced a whole series of plaster reliefs under the title Self-development of the Material, but she also used plaster fragments combined with other materials. Wall Formed by Material Running Down in the Wind-swept Desert of 1970, in which a photograph is combined with plaster relief is a particularly beautiful, almost lyrical landscape from the same period when she started the series of sculpted pieces made of white cement. These are small-scale models that can be enlarged as much as one pleases, offering varied and intriguing spectacles from every angle, including high above, to which traditional sculpture has rarely paid attention. Another group of works is made up pieces comprising a variety of irregular forms or figures compressed into a definite framing shape: Dense Structure and Collected Power are both dated 1969. The same is also seen in her large-scale coloured abstract paintings. Some works reveal their intention int he very title they have been given: The Tiny World of the Subconscious-Diversity of Parts Arranged in a Uniform Whole (1972). All these pieces draw attention to the three principal concepts of movement, structure and tension, all three of them forces that form and sustain a work and all three present in Katalin Hetey’s pieces. The trinity of movement, structure and tension has offered a virtually endless opportunity for variation leaving the artist to ask herself only what she wants to say; with what idea or personal confession about the world can she find to grasp something essential affecting us all. That is, the relationship of the Part and the Whole.

Hetey has referred in an interview to the major effect on her of German physicist Werner Heisenberg’s book, The Part and the Whole. I myself would be wary of making any pronouncements about the connections between atomic physics, philosophy and art, but the loss of the Whole, the new relationship between the Part and the Whole, the fragmentariness of existence is an experience of the modern human condition. In Hungary, even social scientists love to wheel out the poet Endre Ady, who with impressive acuity already pinned down that awareness int he early years of the twentieth century: „Ev’ry whole has shattered / Ev’ry flame flickers just in parts,” he wrote, at a time when such anidea was becoming axiomatic. The torso as raised to a self-sufficient genre within sculpture, exemplifies how the fragment is capable of reflecting the magnificence of what used to be Whole. (Rilke discerned this and captured it in „Archaic Torso of Apollo”). Modern man, and modern art, has accepted such fragmentariness, but Katalin Hetey seems to turn against that trend. The relationship of the Part to the Whole in her work is in constant dialogue rather than expressed as a fixed and accepted reality. Since 1970 she has worked continuously on defining that new kind of relationship through the pieces of that series.

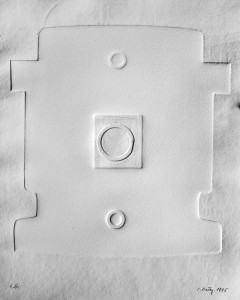

The early parts of the Part and Whole series are spherical bodies cast in bronze which are composed of moveable elements of cylinders and arched forms. By pulling these apart, sculptures of variable form arise from one and the same mass while the space that surrounds the closed form of the sculpture pervades its interior and becomes a part of the sculpture. This world of organic forms was supplemented int the early 1980s by a geometric variand. Lucia Moholy.Nagy (László Moholy-Nagy’s first wife) asked Katalin Hetey to produce for her collection a spatial composition which consisted of two industrial forms and two cubes, giving special regard to the variations that resulted from displacements. This was the starting point for the series of geometric works entitled Part and Whole in which the framing form is a cylinder or cube whereas the partial forms can not only be pulled out but can also be made to turn around the body’s axis. A general feature of the series, then, is that the framing form of the sculpture (sphere, prism, cube, cylinder) is always a circumscribed figure, the inner core of which is made up of parts. Those parts are moveable, so that within any given sculpture lies the potential for various sculptures. Inherent int he body of a permanent sculpture is the potential for unlimited variation, the unlimited possibility of remodelling which, through the independence of the parts, always creates a new Whole. Mass and space, outside and inside, incessantly transform into one another, and out of this delicate interplay emerges the tension of structure and movement. We feel that each and every variant is a self-standing and complete Whole, though knowing that this is merely a momentary state in which the parts find themselves.

The formal inspiration for the series is the world of machines, of industrially created forms and movements. Hetey has spent a great deal of time in factories and workshops, having also worked in the Agricultural Machinery Works and the Carriage & Wagon Works in Győr. She was fascinated by the „world of movement” of factories, with finished products constantly giving her new ideas. After bronze her favourite materials have become iron, aluminium and, above all, steel. The Mono Gallery assembled a small collection of the geometric steel sculptures. Visitors could not move the pieces, but as there are four specimens of each sculpture it was possible to see four versions of the same work next to each other.

„This is the material that provides the cleanest surface, working through its cold beauty, its gentle shine and its strong tension. I sense energies inside it; it compels me to compose the most precisely. Its cleanness is not emotional, not romantic, and it spares me from having to be garrulous,” Hetey comented in an interview.

Ildikó Nagy